Our History

A Legacy of Growth and Service

The MAC was established in 1943 by the State of Minnesota to operate as an airport authority serving the greater Minneapolis-St.Paul area. Originally consisting of Wold-Chamberlain Field (now MSP Airport) on the west side of the metro, and Holman Field on the east side (now St. Paul Downtown Airport), the MAC expanded into the broader metro region by adding five additional general aviation airports.

What preceded the MAC?

The Metropolitan Airports Commission (MAC) marks its 75th anniversary this year (2018), but the idea of creating a single government entity to own and operate Twin Cities’ airports only came about with some diplomacy following years of spirited competition.

Long before the MAC became the airport’s owner and operator, air travel in the Twin Cities went through a series of boom-and-partial-bust periods. The Roaring 20s, the Great Depression and the build-up to World War II all influenced the growth of what is now Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport (MSP).

Out of those years emerged the need to develop one primary airport for the metropolitan area and to create a governing board to promote the growth of aviation in the Twin Cities. But getting there was more a process than a straight path.

Here’s how it began.

MSP traces its roots to the demise of the Twin Cities Motor Speedway (pictured above), which operated on the airport site starting in 1915. The Speedway went bankrupt in 1917 after a brief two-year run, and civic leaders saw an opportunity for a new landing strip to attract more airmail service.

Speedway Field later was renamed Wold-Chamberlain Field to honor two Minneapolis-born aviators killed in World War 1. Wold-Chamberlain Field over the next decade developed on that 160-acre parcel and grew along with an airmail route to Chicago.

During the prosperity of the 1920s, airfield use continued to grow, and Northwest Airlines -- whose acquirer Delta Air Lines still is the largest air carrier at MSP -- formed in 1926 as Northwest Airways.

Col. Lewis Brittin, Northwest’s founder, based the company at Wold-Chamberlain and won the contract for airmail service to Chicago with support from Henry Ford, the automotive industry pioneer.

Both Minneapolis and St. Paul had a hand in the operation of Wold-Chamberlain in the early years. In 1926, the city of St. Paul pulled out of its participation at Wold-Chamberlain and worked to develop an airfield closer to its core downtown area. It was thought having its own airport near the city center would give St. Paul businesses a competitive edge.

Holman Field, across the Mississippi River from downtown, would become a major draw for airmail and airline service. The competition between the two airports would later contribute to the formation of the MAC.

Northwest’s first passenger flight occurred on July 5, 1927, with service from St. Paul to Chicago. A one-way ticket cost $50, which adjusted for inflation would be $708 today. The flight took 12.5 hours with stops in La Crosse, Madison and Milwaukee.

St. Paul’s withdrawal from Wold-Chamberlain created a need to change management of that airport. The Minneapolis Park Board was the only municipal agency that had authority to buy land outside the city limits and was seen as the best choice to operate the airport.

The Park Board bought the airfield for $165,000 in 1928, as the 9th Naval District was announcing plans to establish an air squadron at Wold-Chamberlain. That and other military-related developments at the airfield would influence MSP’s fast growth during World War II.

During the late 1920s, each of the Twin Cities’ two primary airports continued to grow its own base of business. In the summer of 1929, statistics from a one-week period in July showed Holman Field with 82 airline operations and Wold-Chamberlain with 96.

Wold-Chamberlain also had 307 sightseeing operations that same week. The sight-seeing trips typically lasted 7 to 15 minutes and cost $1 or $2.

Air carriers handled the two Twin Cities’ airports differently. Some air carriers served one airport or the other. Northwest and a few others tried to serve both.

The U.S. Postal Service also decided in 1937 that airmail stops would alternate between Wold-Chamberlain and Holman Field -- if the St. Paul airfield was improved.

Locally, the competition was seen as healthy. In the bigger picture of national aviation, though, some local leaders believed the Twin Cities were hurting their ability to lure more air service and business.

In the summer of 1937, the Minneapolis Star reported that the present Wold-Chamberlain facilities “are admittedly taxed to near capacity.” Both Northwest Airlines and Hanford Airlines, which hauled airmail, operated at the airfield. Airport managers made plans for land purchases south of the existing airfield.

Ideas were floated in the early 1940s regarding how to enable airport growth once World War II ended, and a committee formed by the Park Board recommended having one joint airport for the Twin Cities.

“(Wold-Chamberlain) is nearly equidistant from the loop districts of Minneapolis and St. Paul and the running time from each of the loop districts to and from the airport is substantially the same,” the committee noted. “In its enlarged aspect it can adequately serve both cities.”

That led to a legislative proposal to authorize “first-class” cities to issue up to $3 million in bonds for airports.

As the legislative will to help establish airports grew stronger, area leaders looked for a way to unify the Twin Cities and the surrounding metro area behind one primary airport property.

St. Paul Downtown Airport (Holman Field)

In its early days St. Paul competed with Wold-Chamberlain for the dominant position in airmail delivery and commercial air travel in the Twin Cities. But the formation of the MAC in 1943 also supported the ongoing development of MSP, which had more room to grow and was centrally located between the two downtowns.

For much of its history the St. Paul Airport grappled with the threat of spring floods, which have washed across the airfield many times in the last 100 years. Major floods in 1952, 1965, 1969, 1997 and 2001 all led to weeks or months without operations at the airport.

The 1965 flood was the biggest attention-grabber. The month of March 1965 was a record-setter for snow, with 51 inches falling in the St. Cloud area and 66 inches in Collegeville. A rapid springtime warmup followed.

On April 16, 1965, the Mississippi River was 12 feet above flood stage at downtown St. Paul Airport. That flood and several others provided motivation to find a long-term solution.

In 2007-2008, after a lengthy planning process, a new floodwall was constructed. The floodwall has been deployed multiple times since to protect the airport from flooding.

With reliable year-round operations secured, the St. Paul Downtown Airport has seen significant new investment in recent years. That includes new hangars built by corporations, which account for about 80 percent of the airport’s operations.

St. Paul Downtown Airport is the only MAC Reliever Airport having a runway longer than 5,000 feet. As such, it is a key base for corporate jets and business aviation. It is also the only MAC Reliever Airport that hosts a restaurant, Holman’s Table.

Flying Cloud Airport

In 1941 the U.S. Navy reached an agreement with Martin Grill to conduct training flights on a grass strip on his farmland in modern-day Eden Prairie. Grill later sold the site to American Aviation Inc., a private enterprise.

Originally, the airport was going to be called Southwest Minneapolis Airport. Airfield manager John Stuber gave it the “Flying Cloud” name.

With flight activity increasing in the late 1940s, the MAC acquired Flying Cloud in 1948 and paved it the next year.

In the late 1960s and 1970s the airport was home to eight very popular flight schools, as piloting became a popular career choice for veterans returning from service in Vietnam. The airport’s location near the growing Twin Cities area also drew a steady stream of student pilots.

Flying Cloud’s air traffic in that era is hard to imagine by modern standards. Eden Prairie remained largely undeveloped in the 1960s, and in 1966 Flying Cloud Airport ranked second to only Chicago’s O’Hare Airport as the busiest airfield in the central United States.

In 1968, Flying Cloud Airport had 446,198 take-offs and landings, or operations. By comparison, last year MSP had 303,884 operations.

Today Flying Cloud Airport today is primarily a recreational flying hub and also houses a number of corporate jets for businesses in the southwest metro area. The airport handled 131,593 aircraft operations in 2021.

Crystal Airport

In the 1920s the city of Crystal’s first airport was located near the modern-day intersection of W. Broadway and 49th Avenue N.

To make way for suburban expansion, the airport later moved to its current location north of Bass Lake Road.

The MAC acquired the airport in 1948 to serve the northwest metro area. The airport remains a popular hub for recreational flying, and has three runways: two paved and one turf – the only turf runway in the MAC system.

Crystal Airport’s control tower is operated by federal employees and saw 37,845 aircraft operations in 2021.

Lake Elmo Airport

During WW II, land not far from the current airport was used by the U.S. military for training flights.

The MAC acquired land for the current airport in 1949, paying $38,300 for 160 acres. The airport opened two years later. Another 470 acres were added in 1966 to create the present-day airport.

Today Lake Elmo is a recreational and training airport. A new, longer Runway 14/32 opened in 2023.

The airport has about 30,000 take-offs and landings each year.

Anoka County-Blaine Airport

In 1950 the MAC acquired 1,200 acres of farmland in Anoka County to develop a second major airport, which it thought would be needed in 10 to 15 years.

That grand plan never came about, but Anoka County-Blaine Airport did develop into an important reliever airport in the MAC system.

Originally, the University of Minnesota’s flying club had land nearby the current airport but needed room to expand by the late 1940s. Both the University and the MAC ended up acquiring land that became part of the current airport.

In the late 1960s, Anoka County-Blaine Airport took 2,500 feet off the south end of the runway and added the same length to the north end, moving the runway farther away from the city of Mounds View, located to the south. A golf course on the airport’s northern edge also serves as a buffer for neighborhoods in Blaine that have been built over the years.

As part of the dispute with Mounds View, the state passed a law in the year 2000 that places a 5,000-foot limit on runway lengths for “minor airports” that is still in place today. All the MAC’s reliever airports are considered “minor” for that purpose except St. Paul Airport.

Airlake Airport

Airlake Airport was originally a private airfield built by Bloomington-based Hitchcock Industries and open to the public.

As pilot training activity picked up after the Vietnam War with returning veterans and the GI Bill, the MAC saw a need to add an airport with an instrument landing system (ILS) for training purposes. At the time, only MSP had that equipment.

The 25-mile limit to the MAC’s authority was changed to 35 miles in the mid-1970s. That enabled the 1979 acquisition of Airlake, which is located in Lakeville, almost 29 miles from Minneapolis’ City Hall.

The Airlake acquisition came a year after the crash of an airliner in San Diego that had collided with a private plane on a training flight at the San Diego airport.

The Federal Aviation Administration announced soon after that it would help improve 86 satellite airports around the country to move small planes away from major airports.

The new system at Airlake diverted about 60 training flights a day away from MSP.

The relievers adjust to changes in the air

The MAC’s reliever airports today are in a different mode of operations than they were even 15 years ago.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, rising fuel costs and the deep recession led to decreased flying activity. An aging base of recreational pilots is also shrinking the number of users of general aviation airports in the Twin Cities and nationally.

While the volume of recreational flying is down compared to historical levels, flight training, business and corporate activity is up at many of the MAC’s reliever airports.

Those business clients are making new investments in the reliever airports, led by St. Paul and Flying Cloud. The MAC has also continued to improve the airports, highlighted by runway extensions at Anoka County-Blaine in 2008 and at Flying Cloud in 2009, accommodating growth in corporate traffic. Recent runway work at the St. Paul Downtown Airport reconfigured intersecting runways and improved safety.

1940s

The Metropolitan Airports Commission didn’t come into existence with out a push by Northwest Airlines and some pulling by then-Gov. Harold Stassen.

Aviation in the Twin Cities area in the early 1940s was growing through commercial flights, airmail service and an ever-increasing number of military operations. Wold-Chamberlain Field, soon to get a new name, was already a major flight-training center for the military.

The idea of making the Twin Cities region a leading aviation hub had been discussed for years. Minnesota Gov. Harold Stassen spoke once of watching planes land at St. Paul’s Holman Field in the 1930s, and then 15 minutes later take off for Wold-Chamberlain less than 12 miles away.

“I recognized how illogical that was from the stand point of air travel,” Stassen said. “So when I was elected governor in 1938 I decided there ought to be one major municipal airport for the Twin Cities area and that it should be under a special municipal airport commission.”

In the same era, Northwest began using its influence to push for a single Twin Cities airfield.

In 1941, the St. Paul City Council met to discuss Northwest’s plan to withdraw from Holman Field that fall and serve the Twin Cities through Wold-Chamberlain only. As Northwest ended all service at Holman Field in November 1941, the annual passenger count at Wold-Chamberlain was 114,000 and projected to increase to 800,000 after the war.

In January of 1943, the Minneapolis Tribune ran a story with the headline “NWA Chief Proposes Gigantic Expansion of Minneapolis Airport.”

Croil Hunter, then the president of Northwest Airlines, said the expansion of Wold-Chamberlain was necessary to satisfy existing commercial and military aviation needs.

The growth plan would also establish the airport as a “super airdrome” for international air commerce, he said.

Holman Field in St. Paul, he said, “will qualify in the post-war era as a busy port for handling flying freight cargoes and much local air commerce.”

Believing that the Twin Cities had missed becoming a big hub for rail traffic, civic leaders were determined not to miss the boom in aviation and airline service for lack of a major airport.

That push required concentrated air service at one location, a political need for an airfield equidistant from downtowns of both Minneapolis and St. Paul, and enough room for expansion to fulfill the vision of an international hub.

By 1943, the idea had gained momentum. In Stassen’s plan, the commission owning and operating the airport would derive its authority from the state – not from a municipality, as is common in many cities around the United States.

Another motivation for a state-authorized airport was better access to the government funds needed to build a large facility. The initial act establishing the MAC allowed the state to issue bonds for airports, and gave the governor $1 million for the Minnesota Metropolitan Airports Fund to be spent at airports statewide.

Stassen said he was looking forward to the day when the Twin Cities would be a jumping off point for air travel to “the Orient and link to East Asia flights and South America.”

As the 1943 Minnesota legislative session began, representatives of Minneapolis and St. Paul met with Stassen to go over proposed legislation to set up a joint “MSP airways commission.”

At the time, Wold-Chamberlain Field was controlled by the Minneapolis Park Board, and the city of St. Paul controlled Holman Field. The new law would convert control of those facilities to the new commission.

The Minneapolis Tribune reported that the commission that Stassen envisioned would work in harmony on a post-war airport program for the Twin Cities and have powers to include “acquiring property, build and equip airports, take over existing airports and hire a manager for them.”

Stassen’s idea for a commission also had the support of Northwest Airlines.

As the airports commission bill moved through the State Capitol and was approved by the Senate, the Minneapolis Tribune called it “the most important legislation of the session and will enable Minnesota to take front rank in the postwar air transport picture.”

The legislation establishing the MAC won final approval on April 19, 1943 and the law took effect on July 6, 1943.

Despite the passage by the Legislature, the MAC’s early days were not drama-free. The same month that the MAC came into existence, Gov. Stassen – the MAC’s key supporter -- resigned his office to serve as a Naval officer in WW II.

And days before the Minneapolis Park Board was to relinquish control of Wold-Chamberlain to the MAC, lawsuits were filed challenging the move. The lawsuits questioned the constitutionality of portions of the law that established the MAC.

Ultimately, the state and the MAC prevailed, and in August 1944, the MAC officially assumed control of Wold-Chamberlain and Holman Field.

Northwest continued to grow at Wold-Chamberlain through the 1940s, but the airport’s biggest user remained the military. As late as 1947, military flights still made up almost half the aircraft operations at Wold-Chamberlain.

After the war, scheduled commercial service to Tokyo, Seoul, Shanghai and Manila began on July 15, 1947 on a 50-passenger Northwest DC-4.

To reflect the airport’s new ties to destinations overseas, the airport’s name was changed to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport/Wold-Chamberlain Field in 1948.

When the Metropolitan Airports Commission first came into existence in 1943, the organization operated Wold-Chamberlain Field (which is now Minneapolis-St. Paul International) near Minneapolis and Holman Field in St. Paul.

The law that created the MAC authorized the organization to develop other airports within 25 miles of the core of Minneapolis and St. Paul. (Later legislation expanded that authority to within 35 miles of each city’s downtown.)

By the time WW II ended, the MAC was preparing to acquire several area airports. As demand for general aviation flights increased in the metropolitan area, along with commercial air service, it became clear that Wold-Chamberlain would not have the capacity to accommodate all the area’s aviation needs.

Following -- in order of when the MAC acquired the land for each airport -- are brief histories of the six reliever airports in the MAC’s system.

Modern details about each airport can be found at this website.

St. Paul Downtown Airport (Holman Field)

In its early days St. Paul competed with Wold-Chamberlain for the dominant position in airmail delivery and commercial air travel in the Twin Cities. But the formation of the MAC in 1943 also supported the ongoing development of MSP, which had more room to grow and was centrally located between the two downtowns.

Pictured: An airport employee at St. Paul's Holman Field checks a weather station in the 1920s.

For much of its history the St. Paul Airport grappled with the threat of spring floods, which have washed across the airfield many times in the last 100 years. Major floods in 1952, 1965, 1969, 1997 and 2001 all led to weeks or months without operations at the airport.

The 1965 flood was the biggest attention-grabber. The month of March 1965 was a record-setter for snow, with 51 inches falling in the St. Cloud area and 66 inches in Collegeville. A rapid springtime warmup followed, unlike this year.

On April 16, 1965, the Mississippi River was 12 feet above flood stage at downtown St. Paul. That flood and several others provided motivation to find a long-term solution.

In 2007-08, after a lengthy planning process, a new floodwall was constructed. The floodwall has been deployed multiple times since to protect the airport from flooding.

With reliable year-round operations secured, the St. Paul Downtown Airport has seen significant new investment in recent years. That includes new hangars built by corporations, which account for about 80 percent of the airport’s operations.

St. Paul Downtown is the only MAC airport classified as an “intermediate” airport, having a runway longer than 5,000 feet. As such, it is a key base for corporate jets and business aviation.

Flying Cloud Airport

In 1941 the U.S. Navy reached an agreement with Martin Grill to conduct training flights on a grass strip on his farmland in modern-day Eden Prairie. Grill later sold the site to American Aviation Inc., a private enterprise.

Originally, the airport was going to be called Southwest Minneapolis Airport. Airfield manager John Stuber gave it the “Flying Cloud” name.

With flight activity on the increase in the late 1940s, the MAC acquired Flying Cloud in 1948 and paved it the next year.

In the late 1960s and 1970s the airport was home to eight very popular flight schools, as piloting became a popular career choice for veterans returning from service in Vietnam. The airport’s location near the growing Twin Cities area also drew a steady stream of student pilots.

Flying Cloud’s air traffic in that era is hard to imagine by modern standards. Eden Prairie remained largely undeveloped in the 1960s, and in 1966 Flying Cloud ranked second to only Chicago’s O’Hare Airport as the busiest airfield in the central United States.

In 1968, Flying Cloud had 446,198 take-offs and landings, or operations. By comparison, last year MSP had 416,213 operations.

Today Flying Cloud today is primarily a recreational flying hub and also houses a number of corporate jets for businesses in the southwest metro area. The airport handles about 90,000 operations per year.

Crystal Airport

In the 1920s the city of Crystal’s first airport was located near the modern-day intersection of W. Broadway and 49th Avenue N.

To make way for suburban expansion, the airport later moved to its current location north of Bass Lake Road.

The MAC acquired the airport in 1948 to serve the northwest metro area. The airport remains a popular hub for recreational flying, and has four runways: three paved and one turf – the only turf runway in the MAC system.

Crystal’s control tower is operated by federal employees and sees about 40,000 operations per year.

Lake Elmo Airport

During WW II, land not far from the current airport was used by the U.S. military for training flights.

The MAC acquired land for the current airport in 1949, paying $38,300 for 160 acres. Another 470 acres were added in 1966 to create the present-day airport.

Today Lake Elmo is a recreational and training airport, and is in the midst of an environmental assessment that involves reviewing plans to relocate a runway and realign 30th Street North.

The airport has about 25,000 take-offs and landings each year.

Anoka County-Blaine Airport

In 1950 the MAC acquired 1,200 acres of farmland in Anoka County to develop a second major airport, which it thought would be needed in 10 to 15 years.

That grand plan never came about, but Anoka County-Blaine did develop into an important reliever airport in the MAC system.

Originally, the University of Minnesota’s flying club had land nearby the current airport but needed room to expand by the late 1940s. Both the University and the MAC ended up acquiring land that became part of the current airport.

In the late 1960s, Anoka County-Blaine Airport took 2,500 feet off the south end of the runway and added the same length to the north end, moving the runway farther away from the city of Mounds View, located to the south. A golf course on the airport’s northern edge also serves as a buffer for neighborhoods in Blaine that have been built over the years.

As part of the dispute with Mounds View, the state passed a law in the year 2000 that places a 5,000-foot limit on runway lengths for “minor airports” that is still in place today. All the MAC’s reliever airports are considered “minor” for that purpose except St. Paul.

Airlake Airport

Airlake Airport was originally a private airfield built by Bloomington-based Hitchcock Industries and open to the public.

As pilot training activity picked up after the Vietnam War with returning veterans and the GI Bill, the MAC saw a need to add an airport with an instrument landing system (ILS) for training purposes. At the time, only MSP had that equipment.

The 25-mile limit to the MAC’s authority was changed to 35 miles in the mid-1970s. That enabled the 1979 acquisition of Airlake, which is located in Lakeville, almost 29 miles from Minneapolis’ City Hall.

The Airlake acquisition came a year after the crash of an airliner in San Diego that had collided with a private plane on a training flight at the San Diego airport.

The Federal Aviation Administration announced soon after that it would help improve 86 satellite airports around the country to move small planes away from major airports.

The new system at Airlake diverted about 60 training flights a day away from MSP.

The relievers adjust to changes in the air

The MAC’s reliever airports today are in a different mode of operations than they were even 15 years ago.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, rising fuel costs and the deep recession led to decreased flying activity. An aging base of recreational pilots is also shrinking the number of users of general aviation airports in the Twin Cities and nationally.

While the volume of recreational flying is down, business and corporate activity is up at many of the MAC’s reliever airports.

Those business clients are making new investments in the reliever airports, led by St. Paul and Flying Cloud. The MAC has also continued to improve the airports, highlighted by runway extensions at Anoka County-Blaine in 2008 and at Flying Cloud in 2009, accommodating growth in corporate traffic. Recent runway work at the St. Paul Airport reconfigured intersecting runways and improved safety.

A recently completed economic impact study of the reliever airports found that together they contribute an estimated $756 million annually to the Twin Cities-area economy, along with 1,030 direct jobs.

Broken down by each airport:

Airlake Airport (in Lakeville and Eureka Township)

Direct Jobs: 31

Total Jobs: 104

Total Economic Output $13.2 million

Anoka County-Blaine Airport

Direct Jobs: 130

Total Jobs: 560

Total Economic Output $118 million

Crystal Airport

Direct Jobs: 100

Total Jobs: 320

Total Economic Output $71 million

Flying Cloud Airport (in Eden Prairie)

Direct Jobs: 340

Total Jobs: 1,190

Total Economic Output $229 million

Lake Elmo Airport

Direct Jobs: 14

Total Jobs: 60

Total Economic Output $12.8 million

St. Paul Downtown Airport

Direct Jobs: 410

Total Jobs: 1,430

Total Economic Output $312 million

1950s

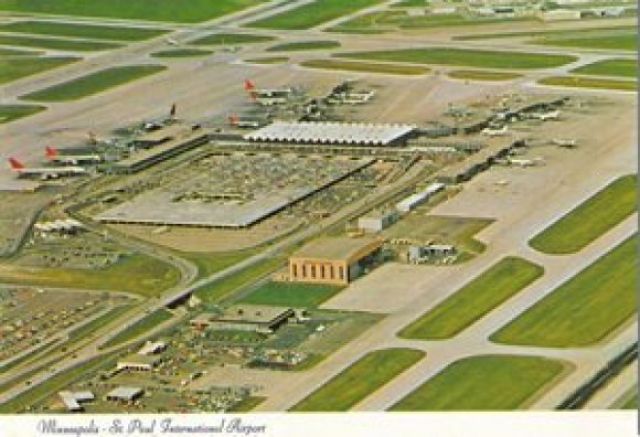

As the Twin Cities boomed in the 1950s, the Metropolitan Airports Commission found itself working to manage fast growth at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport.

Thousands of service men and women returned from duty overseas as World War II ended, and the 1950s saw tremendous growth in the Twin Cities area, with the population rising 26 percent during the decade to 1.9 million.

Northwest Airlines also saw its passenger numbers continuing to climb, aided by its strong market position on flights to Asia.

And Northwest wasn’t alone. Four scheduled airlines operated at MSP after WW II, and the original terminal building on the west side of the airfield became stretched beyond capacity by the mid-1950s.

The novelty of flight was still strong in 1950, the first year the airport’s observation deck was open on the west side of the airfield. The deck drew 264,000 visitors that year -- an average of more than 700 per day.

For the airlines, MSP had other draws. A Mississippi River flood in 1952 prompted Northwest Airlines to look for a new location for its maintenance base at the St. Paul Airport, which was susceptible to high water.

In the mid-1950s construction started on a new Northwest Airlines overhaul maintenance base at MSP and the airline moved the St. Paul maintenance operations to the new facility in 1959. New general offices for Northwest and the maintenance base amounted to an $18 million investment and solidified MSP as the airline's home base.

In 1956, Northwest Airlines had 5,500 employees globally and was growing rapidly. Two years later, Northwest started modernizing its fleet, adding Lockheed Electras and Douglas DC-8s to the existing fleet of StratoCruisers.

By 1955 MSP had passed a milestone by serving more than 1 million passengers annually. That same year, 427 acres of Fort Snelling were deeded to the MAC, providing room for expansion of the airfield and needed facilities.

Planning the new terminal

Studies of a new, modern facility began after forecasts projected that passenger counts would reach 4 million by 1975. The airlines supported the idea of a new terminal and the entire project was designed with future expansions in mind, including space for ticket counters, offices, waiting areas and more concessions.

The new terminal came with an $8.5 million price tag and was designed to handle 14,000 passengers per day.

Compared to other airports, the key design component that set the new terminal apart was putting passenger services on the top level, with baggage and ground transportation services on the lower level.

Ground was broken in October 1958 on the east side of the airfield. The expansion plan, which totaled $47 million, also included a new control tower, access roads and upgrades to runways and taxiways.

Out front, the terminal had a new 2,500-space parking lot, also designed with room for expansion.

Police and fire service grows along with the airport

The Airport Police Department started in 1947 when the MAC hired two officers to patrol the small terminal on the west side of the airfield and the adjacent parking lot.

The job description included turning off the lights each evening before they went home.

The police department continued to add an officer or two each year during the 1950s, and then added 10 in 1962, the year the new terminal building opened. That brought the total to 25.

Police department milestones included the formation of a detective division in 1974 and a SWAT team in 1978.

For years, the police facilities were housed on the baggage claim level at Terminal 1. In 1984, police administration moved to the mezzanine level and the communications center moved to a shared space with Airside Operations.

Today, the Airport Police Department includes 115 sworn officers and 70 non-sworn personnel. They respond to a wide variety of calls as 38 million people pass through MSP annually.

In its early days, MSP relied on the Minneapolis Fire Department for fire service. In the 1950s, Minneapolis had a fire station at the Naval Air Station and responded to calls from that location.

The Air Force eventually took over the firefighting responsibilities at the airport.

With the new terminal under construction in the late 1950s, the MAC moved toward launching its own fire department. In 1961 the Air Force Fire Department’s fire equipment was transferred to the MAC. In 1962, construction of a new fire station near the control tower began.

When runway 17/35 was planned, the airport needed a second fire station, due to an FAA rule that fire crews have to be able to reach the end of each runway within 3 minutes. The MAC built a new fire station next to Terminal 2 in 2005, and the Airport Fire Department administration also is based there.

Today, the Airport Fire Department has 51 employees, including administrative staff. About 70 percent of department calls are medical-related.

The new terminal gives MSP a modern look, room to expand

After more than three years of construction, the new terminal was completed on Jan. 13, 1962. An open house the next day drew a crowd of 100,000. The Augsburg College Band and the Business and Industrial Choral Society provided the entertainment.

The exterior featured the eye-catching “sawtooth” roof with 17 folds, which is still a signature component of the building. The two concourses that extended off the terminal provided a total of 24 gates for aircraft.

The upper-level roadway in front of the terminal came with a state-of-the-art built-in snow-melting system. Services in the ticketing lobby initially included a drugstore and a children’s nursery.

As with all US airports, there were no security checkpoints at MSP until the early 1970s.

Closer to the airport’s two concourses, passengers could find food services including a dining room, snack bar and coffee shop all served by a common kitchen.

Initially, the terminal’s two concourses were called Piers B and C. However, the names sounded too similar on the 1960s public address system used at MSP, and they were changed to Blue and Red – known today as Concourses E and F.

The first flight to arrive at the terminal was operated by Northwest Airlines and arrived a week after the public opening, on Jan. 21.

The projected growth in passenger numbers in the mid-1950s lived up to expectations, as the airport served 756,000 passengers in 1950, booming to 1.8 million in 1960.

The number of carriers serving MSP had continued to expand as well. Eastern Air Lines and Ozark Airlines had entered the market in the late 1950s, and Western, United, North Central and Braniff were also offering flights at MSP.

The first scheduled jet aircraft flight came through the airport on Jan. 5, 1961, as a Northwest Airlines DC-8 stopped at MSP in route to Chicago. Braniff began jet service to MSP four months later.

As the jet age arrived at MSP, neighborhoods around the airport were in the midst of the Baby Boom. As evidence, enrollment in the Richfield Public Schools went from 2,506 in 1950 to 10,055 in 1960.

With more people moving into newly built subdivisions near MSP, airport noise started to attract more attention. That noise, particularly from commercial jetliners, would play a key role in a late-1960s push to move the airport farther away from the urban center.

1960s

The opening of the new terminal at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport in 1962 only marked the beginning of a period of sustained growth.

Passenger numbers continued to increase as more people were drawn to the Twin Cities metro area, and the airlines augmented their flight schedules during the 1960s with more routes served by new, faster jets.

To handle the larger planes, the south parallel runway had been extended to 10,000 feet by the end of 1961.

Braniff Airlines began flying Boeing 720B jets from MSP to Mexico City in 1961, and Western and United followed soon after with additional jet service of their own.

Northwest had earlier introduced service on DC-8s and continued to upgrade its jet fleet throughout the decade. By the early 1970s, Northwest Airlines’ fleet included 15 Boeing 747s and 14 Douglas DC-10s.

After the new terminal opened at MSP, construction projects also began to dot the airfield.

North Central Airlines broke ground in 1967 on a new $17 million main base and headquarters on the south end of the airfield, which opened in 1969. Northwest started work in 1969 on an $18 million hangar expansion to service 747s and DC-10s.

A new concourse opened in 1968 for “transient” aircraft, those operated by airlines that weren’t based at MSP.

The continuing growth wasn’t without complications.

Aircraft noise had been a simmering issue for more than 20 years. In fact, records of public hearings in Minneapolis in 1947 show that people spoke against any further expansion at MSP due to noise.

For the MAC’s leadership, the boom in passenger numbers came to a head in 1967. An FAA forecast on air travel showed that by 1980, MSP wouldn’t have sufficient capacity to meet passenger demand.

At the same time, as jets became common in the skies over the Twin Cities, neighborhood activism increased.

A Minneapolis City Council meeting in 1968 drew 400 people demanding the passage of an ordinance banning air travel over the city.

The ordinance wasn’t enacted, but that type of community pressure led to the formation of the Metropolitan Aircraft Sound Abatement Council (MASAC) in 1969. The council included 13 public representatives and 13 from the airlines.

The MASAC worked collaboratively to come up with several procedures to reduce aircraft noise near the airport. The group’s efforts led to a reduction in the number of training flights at MSP and contributed to the addition of a noise abatement specialist to the MAC staff. Later, the MAC also established a noise abatement hotline to handle complaints.

In the years that followed, the MAC would work with the community to implement a noise program – including extensive mitigation efforts – that would become a national leader known for its innovation and responsiveness.

The Ham Lake proposal

Given the backdrop of demand for more flights and noise concerns from surrounding neighborhoods, the MAC began a search for a new airport location. Leaders looked for a large site located far away from residential areas, while also allowing the MAC to finance the project with existing sources of revenue.

Studies of the Twin Cities area soon identified a site in Ham Lake, an undeveloped area located about five miles north of Blaine.

The site was located northeast of the intersection of Hwy. 65 and Bunker Lake Road, and bounded by the Carlos Avery Wildlife Management Area to the east.

In the late 1960s, even though the city of Blaine was in the early stages of planning, its build-out had not even begun. And compared to the south metro, there was less demand from developers in the far northern suburbs due to the presence of scattered wetlands.

There were four public hearings in 1968 following the MAC’s announcement of its intent to build a new airport in Ham Lake.

The City of Anoka and the Anoka Chamber of Commerce supported the plan. Spring Lake Park and Columbus Township – which is located near the actual site – opposed it.

The Ham Lake town board voted to seek to delay the project and asked the State Legislature to examine what was behind the state’s intent when it created the MAC back in 1943.

The planning continued and the MAC began working to have its jurisdictional area of a 25-mile radius from the core of both Minneapolis and St. Paul increased to 35 miles. That change ultimately became law in 1974.

Also in 1969, the Minnesota Legislature took up three separate bills from 13 different metro area legislators, two of the bills dealing solely with the composition of the MAC’s board of commissioners. The suburbs wanted more of a voice in the operation of MSP and plans for the future.

None of the bills passed, but the ball had started rolling for broader representation on the MAC’s board.

Ultimately, the more powerful opposition to the Ham Lake plan came from the Metropolitan Council, which had been established in 1967, and from the airlines serving MSP.

The Met Council had a key role in long-term planning in the metro area, and expressed concerns about environmental impacts to the Ham Lake area and plans to finance the new airport.

From 1948 to 1958, the MAC issued bonds totaling $10.2 million to pay for construction and other projects, which were paid for by property owners in the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. But as the 1960s progressed, the airport embraced a self-funding model that relied exclusively on rents or fees collected at the airport.

The airport’s existing revenue stream was used by the MAC to operate MSP, and questions arose about whether that income could simultaneously support the issuance of bonds to build a new airport. Some area leaders argued that the MAC’s ability to tax property would need to be expanded more broadly in the metro area to build in Ham Lake.

The airlines were initially cool to the idea of a new airport. Many of the airlines had recently invested in new facilities at MSP and weren’t anxious to make a move north. Also, airline leases to operate at MSP weren’t open for renegotiation until the summer of 1973.

As the Ham Lake plans progressed, Northwest Airlines sent a telegram to the MAC's Board of Commissioners, threatening to stop a $22 million construction project at MSP.

Also at issue: the distance of any new airport from the urban center. A 1970 consultant’s report, done for the MAC, noted that “if the (new) airport is over 30 miles from the city center, there is difficulty making the airport an integral part of the community."

MSP’s location provides convenience for its users, and the drive time to any new airport and its proximity to jobs and housing also needed to be considered, the report noted.

In votes taken in both 1969 and 1970 on proposals from the MAC, the Metropolitan Council vetoed plans to build a second commercial airport at Ham Lake.

In 1972, after further negotiations, the MAC and the Metropolitan Council did reach an agreement on the Ham Lake site.

A few things had changed by that time. A mild recession that began in 1969 led to doubts about forecasted growth in passenger numbers, and the airlines’ opposition to Ham Lake had only increased.

Ultimately, the MAC decided not to move forward with the Ham Lake plan. Today, the Ham Lake area considered for a new airport is full of subdivisions with residential homes.

The idea of relocating the airport would be revisited 20 years later, as the airline industry and the airport continued to grow.

In 1989, the Minnesota Legislature passed the Metropolitan Airport Planning Act. That began a process that evaluated whether to expand MSP at its existing site or build a new airport farther away from the Twin Cities’ core.

Future stories in this monthly series will provide more detail on that era of airport planning.

Hollywood comes to MSP

The filming of the blockbuster movie “Airport” at MSP in 1969 shed a different light on the airport.

The film, which became the first in the 1970s genre of disaster films, had a sizable cast with big names including Dean Martin, Burt Lancaster and Jacqueline Bisset.

The plot lines included an airport manager (Lancaster) trying to keep a fictional Chicago-area airport open during a snowstorm. Also, a passenger aboard the plane -- where Martin is the co-pilot -- threatens to blow up the aircraft.

MSP was picked as the key filming location largely for its winter weather. However, when filming started the weather didn’t cooperate. Many MAC snowplow operators were involved in filming snow scenes, but film director George Seaton had to use plastic pellets of “snow” to simulate a blizzard.

The climactic scene features a landing in a plastic snowstorm at MSP, which you can watch here.

The movie received a lukewarm reception from critics, but audiences loved it.

Costing $10 million to produce, the film’s box office was more than $100 million, making it the second-highest grossing film of 1970. Helen Hayes, who portrayed a stowaway on the plane, won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. The film was also nominated for several other Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

More changes coming for MSP in the 1970s and beyond

Compared to today’s airline industry, air travel in the early 1970s was still a novelty for most Americans.

Estimates from 1973 show that no more than 20 percent of Americans had ever flown on an airplane. Flights were relatively expensive and far-flung vacations were not the norm.

By the year 2000, 50 percent of Americans had taken at least one round-trip flight in the last year. In addition, the number of air passengers in the US would triple between the early 1970s and 2011, continuing a fast pace of change for airlines and airports.

Sources for this article:

Minnesota Historical Society Archives.

MAC meeting minutes.

Speas Associates report, 1970.

"America's North Coast Gateway," by Karl Bremer.

1970s

As the controversy about a new site for an airport in Ham Lake faded, the MAC pushed into the 1970s with an eye toward well-managed growth.

Airlines continued to modernize their fleets and add destinations, while passenger counts at MSP grew steadily. The four-million-passenger level predicted for 1975 had been surpassed in 1967 and the MAC worked with the airlines to add gates at the terminal and hangars on the airfield.

In the early 1970s, MAC leaders made several accommodations for the airport’s growing number of passengers. In November of 1970, as the Vietnam War continued, the “Servicemen’s Center” opened at MSP. Volunteers staffed the center 24 hours a day. In its first year, the center served more than 18,000 military personnel passing through the airport.

The airport also continued to reach out to community members upset about airport noise. In 1971, the MAC hired Claude Schmidt as its first director of environment and noise abatement.

In a news story about his new post, Schmidt said he hoped to reduce the number of military flights over time, re-route flights over less-populated areas and reduce nighttime engine run-ups, which are used to test engines.

Pictured: The North Central Airlines hangar in the 1970s.

The MAC’s noise program, a pioneering effort among U.S. airports, attracted increasing amounts of media attention throughout the 1970s. The Metropolitan Aircraft Sound Abatement Council met regularly, looking for ways to reduce noise above residential areas.

MSP’s broader growth plan hit a snag when the 1973 oil crisis arrived. Oil-producing countries in the Middle East set an embargo against exports to the US, a response to U.S. support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

Ray Glumack, who at the time was the director of operations for the MAC, told the Minneapolis Star in November 1973 that flights at MSP were being cut back substantially because of the oil crisis. Federal authorities had asked the airlines to reduce aircraft fuel consumption by 25 percent from 1972 levels.

The MAC maintains control of the airports; Hamiel arrives

The idea of moving the airport to Ham Lake in the late 1960s had brought attention to the airport’s operations and planning. However, the airport’s revenues were dedicated to maintaining MSP operations and expanding the current site as needed -- not acquiring another location.

Some legislators and the Metropolitan Council, the regional planning group in the Twin Cities, saw a need for a change.

In 1972, the Metropolitan Council began a push to gain more control over the MAC, along with the area’s transit system and sewer board.

The Met Council wanted the authority to appoint the chairs and members of all three agencies, and authority to review their capital and operating budgets. The Council also wanted more control over plans for a new airport.

In 1973, the Met Council’s efforts to take control of the MAC failed for lack of support from legislators. One change that did become reality involved the MAC’s board of commissioners, which was eventually expanded to include representatives from suburban areas where any new airport would be located.

In 1975, Glumack became the MAC’s executive director, succeeding Henry Kuiti, who had held the post since 1960.

Glumack’s tenure included guiding the airport through the era of airline deregulation and focusing more on the MAC’s noise program, which included hiring Jeff Hamiel in 1977 as manager of noise abatement and environmental affairs.

During the 1970s and into the 1980s, the airport implemented more than 50 strategies to reduce noise. One procedure to reduce noise in 1974 involved having arriving commercial flights approach MSP at a steeper angle, reducing noise for residents several miles from the airport, but not those neighborhoods closest to MSP.

“Some (procedures) worked, some didn’t,” Hamiel said. “But we worked constantly to improve the situation.”

Security screening comes to MSP

Prior to the 1970s, American airports had only minimal security measures in place, and there were no security screenings prior to getting on a plane.

The arrival of security screening stemmed from a rash of hijackings in American airspace, with 159 events from 1961 to the end of 1972.

The majority of those occurred in the 1968-72 timespan, when hijackings to Cuba became increasingly common.

The hijackers were often seeking political asylum in Communist Cuba, or were armed with guns or explosives and seeking to extort money from the airlines. The hijackings typically did not end in tragedy or mass casualties.

The airlines, meanwhile, feared that passengers would be more upset by metal detectors and a delay at the airport than the rare midair diversion of a hijacked flight.

The uneasy tolerance of hijacking ended in November, 1972, when a Southern Airways flight was taken over by three hijackers. The hijackers threatened to fly the plane into a nuclear reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

Early in 1973, the FAA began requiring security screening of all passengers and their carry-on bags. Airlines controlled the contracts for the operation of the checkpoints. Passengers quickly learned that they needed to build in extra time prior to their flight’s departure to clear security.

The Humphrey Terminal’s early days

In 1975, the MAC bought United Airline’s six-year-old hangar with its paraboloid roof and converted it into what would later be named the Hubert H. Humphrey Charter Terminal. It was expected to serve 100,000 passengers per year.

The new international charter terminal was dedicated in 1976. The facility could handle three charter flights at a time, and passengers were transported to the main terminal by a shuttle bus that used a tunnel under the airfield.

The 48,000-square-foot terminal replaced the space at the main terminal that had housed U.S. Customs and arrivals of international charter flights. At the time, MSP served about 60 international charter flights per month.

In August of 1977, the Minnesota Zoo’s two new Beluga whales were unloaded from a plane at the charter terminal, a process that took more than an hour. The whales, transported to Minnesota from Churchill, Canada, on Hudson Bay, were among the zoo’s top attractions in its early years.

This original charter terminal would be replaced in 2002 by a much more modern and spacious building.

Airline deregulation comes to MSP; Republic Airlines forms

Prior to 1978, the federal government controlled airfares, routes and market entry of new airlines. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 eventually brought dramatic change to the airline industry, including increased competition and more airlines flying out of MSP and other airports across the nation.

The first merger of airlines after deregulation occurred in 1979. North Central Airlines and Southern Airways merged to form Republic Airlines, with headquarters at MSP.

Just prior to deregulation, MSP was served by eight mainline carriers and four commuter airlines, Glumack told the Minneapolis Star.

Soon after deregulation in 1978, MSP had 15 major carriers and eight commuter airlines serving the market, with 13 more waiting in the wings and four international airlines looking for access to gates, Glumack said.

Republic Airlines had a large presence at MSP, due to North Central’s history at the airport. But the airline’s largest hub was located in Detroit. Republic also bought out Hughes Airwest in 1980, making the new airline the largest in the country as measured by the number of airports served.

Jet fuel prices had doubled in 1979, but the after-effects of deregulation were playing a large role in the airline market.

Northwest Airlines, which would merge with Republic later in the 1980s, announced a new, broader domestic schedule, serving 20 new domestic markets, and ratcheted up its international destinations as well. That included the first trans-Atlantic passenger service through Detroit and New York to Copenhagen and Stockholm in 1979.

Passenger service to Glasgow soon followed and on June 2, 1980, Northwest flew the first Twin Cities-to-London (Gatwick) direct flight on a Boeing 747.

Sources:

MAC archive materials.

Minneapolis Star newspaper articles.

Minnesota Historical Society archives.

“Northwest Airlines: The first 80 years,” by Geoff Jones.

“America’s North Coast Gateway,” by Karl Bremer.

1980s

(Editor’s note: Following is the seventh in a series of articles regarding how the Metropolitan Airports Commission came into being 75 years ago, and how the commission’s airport system has evolved over the decades.)

As the Metropolitan Airports Commission entered the 1980s, the airline industry was in the midst of upheaval following deregulation in 1978.

With increased competition, several airlines found themselves teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, and consolidations continued following a recession in 1981-82.

The decade also brought a larger and more dominant Northwest Airlines and the promotion of Jeff Hamiel to the MAC’s executive director position, a post he would hold for more than 30 years.

In 1981 Northwest Airlines and Republic Airlines announced plans for separate projects totaling $50 million at MSP, including an addition to Northwest’s maintenance base and a new Republic hangar. At the time, Northwest was also planning a new headquarters on the banks above the Minnesota River in Bloomington, near 34th Avenue, although that project would end up in Eagan.

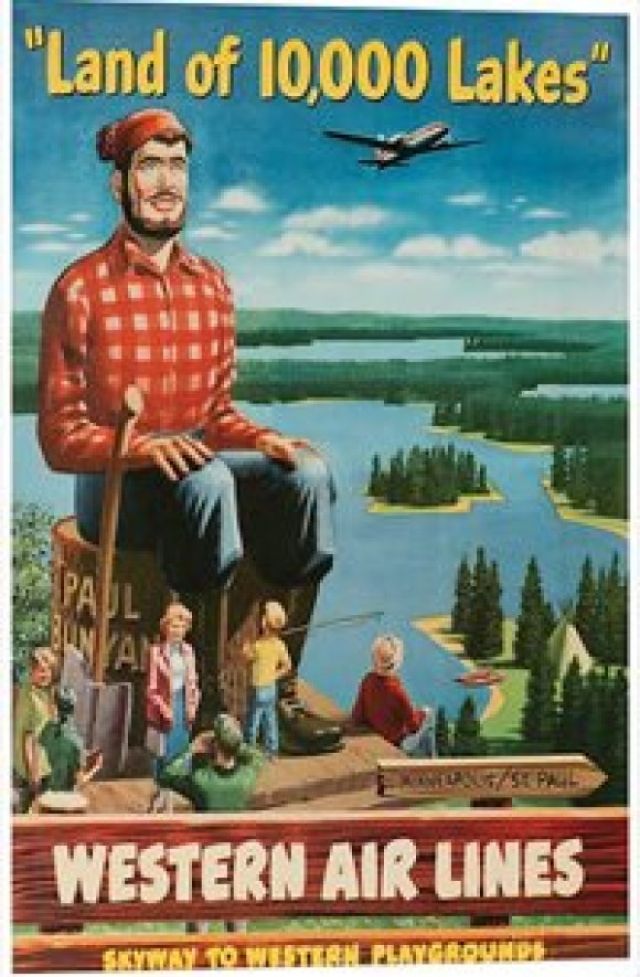

Pictured: An ad from Western Airlines, which served MSP in the 1970s and 1980s. Western merged with Delta Air Lines in 1986.

U.S. airlines lost more than $600 million in 1981, a year of recession and government efforts to curb inflation – the interest rate on mortgage loans averaged 17 percent that year.

To make their far-flung route offerings more efficient, airlines increasingly embraced a hub-and-spoke system, with fleets of aircraft concentrated at major airports that served as connecting points. The model became the norm in the industry for large, networked airlines.

As the market forces of deregulation played out, Braniff Airlines filed for bankruptcy in 1982 -- a move that indirectly led to the formation of Sun Country Airlines in 1983.

Former Braniff pilots came together to launch Sun Country with MSP as its home base. MLT Vacations Inc., a Twin Cities-based provider of flight-and-hotel packages, was a key financial backer.

The charter airline performed well with flights to sunny destinations during Minnesota’s cold-weather months. As Sun Country became more popular, other airlines noticed the trend and competition increased. Sun Country’s original owners put together a deal to sell the airline to Northwest in the mid-1980s, but dissenting shareholders blocked the idea.

Sun Country was eventually sold to B. John Barry, a banker, in 1988. By the early 1990s, Sun Country was the third largest charter airline in the U.S., aided in large part by revenue from military charters during the first Gulf War.

Passenger numbers continued to expand at MSP as the economy recovered from the early 1980s recession, and the MAC worked to meet demand for services. In 1984 a new seven-level, $20 million parking ramp opened at Terminal 1 with 2,000 spaces. The concession program at MSP continued to grow as well, with the first McDonald’s opening in 1985.

That fall, an eight-member search committee led by Carl Pohlad selected a group of candidates to interview for the MAC’s executive director position. In November, Jeff Hamiel, then 38 years old, was selected to lead the MAC, which at the time had 250 employees.

Hamiel had been hired in 1977 by Ray Glumack, the MAC’s former executive director. Over the years Hamiel had held five different jobs at the MAC, the most recent being deputy executive director.

Also in 1985, an independent study of the airport predicted 29 million passengers by 2003, while passenger volume had totaled 11.5 million in 1983. The report spurred renewed talk of the need for a new airport, farther from the Twin Cities’ urban center.

The airport’s dual track planning process did not begin until 1989. However, it actually had its roots in a decades-old lawsuit filed against the MAC, leading to a 1985 Minnesota State Supreme Court decision.

In Ario vs. MAC, the court’s decision in 1985 suggested there was a class of about 27,500 property owners near the airport who might have a common legal standing against the MAC, due to aircraft noise.

The court also found that a decline in the market value of homes affected by airplane noise had not been proven.

With the Ario decision and continuing passenger growth at MSP as the backdrop, in 1989 the Minnesota State Legislature passed the Metropolitan Airport Planning Act, which became known as the “Dual Track Process.”

Essentially, the airport was directed to study whether the best solution for the airport’s future – given the complaints about airplane noise and anticipated growth in passenger numbers – was to either expand the existing airport’s capacity, or build a new airport out beyond existing suburban development.

Northwest and Republic merge

Northwest Airlines and Republic Airlines were both major operators at MSP in the 1980s. As Republic started pulling domestic travelers away from Northwest, a former Republic executive approached Northwest with what was called a “fish-buys-whale” idea.

The plan led eventually to Northwest buying Republic for $884 million in 1986. The deal built up Northwest’s domestic network and gave Republic fliers easier access to Northwest’s international destinations. Northwest dropped the “Orient” from the end of its name after the acquisition.

Republic’s four major hubs had been MSP, Detroit, Memphis and Phoenix -- the first three of which would become the core of Northwest Airline’s hub presence following the purchase. Republic also operated the world’s largest fleet of DC-9s, an aircraft that would have a presence at MSP for years to come.

With the acquisition, Northwest almost doubled in size at MSP and became the unparalleled dominant carrier at MSP.

Northwest Airlines’ leveraged buyout

As the decade closed, the airline industry had one more surprise for MSP.

The 1980s era of leveraged buyouts -- a popular tool for private equity groups -- was near its end. But financiers began eyeing Northwest Airline’s operations and it routes to Asia, which were seen as under-valued.

Gary Wilson, a former NWA board member and Al Checchi (pictured below), a former associate of the wealthy Bass family of Texas, had acquired about 5 percent of NWA stock and were planning a takeover involving a large debt-load.

Marvin Davis, a billionaire real estate developer, was also making a move to acquire Northwest.

Ultimately, the Wilson-Checchi group prevailed, putting together a $3.65 billion leveraged buyout of Northwest. In September of 1989, Northwest CEO Steven Rothmeier and his team resigned, replaced by Checchi and a new management group.

In the early 1990s, the airline would negotiate with the MAC and the state of Minnesota on financial terms to keep Northwest in Minnesota and retain MSP as a key hub.

Sources: MAC archive materials. Minnesota State Historicial Society archives. Newspaper clips, Minneapolis StarTribune; other publications.

1990s

The MAC in the 1990s: A dual track study and NWA negotiations

(Editor’s note: Following is the eighth in a series of articles on the history of the Metropolitan Airports Commission, which is marking its 75th anniversary this year.)

The 1990s opened as the state of Minnesota and the Metropolitan Airports Commission (MAC) began deciding the future of Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport: whether to expand at its existing location or develop a new airport elsewhere.

As that work began, Northwest Airlines sought public financing to expand its presence in Minnesota –financing that later proved important in helping the airline survive a period of financial losses.

Pictured: Samuel Skinner, US Secretary of Transportation, and Jeff Hamiel, CEO and executive director of the MAC, meet in the early 1990s.

Following the purchase of Northwest Airlines in 1989 by Wings Holding, the airline was carrying debt that limited its operations. Northwest lost money in 1990 and 1991, leading up to its request to the MAC and the state of Minnesota for assistance to build Airbus maintenance bases in Duluth and Hibbing, Minn.

Over the course of almost a full year, Northwest and the state negotiated a deal; the incentives package was re-worked several times. At one point a handful of cities and airports around the U.S. were bidding for the planned Airbus maintenance base.

Interested parties included Kansas City, Detroit, Memphis, Seattle, Indianapolis and Milwaukee.

Ultimately, the state of Minnesota approved a $761 million financial assistance package for the airline to reduce debt and build facilities in Northeastern Minnesota, a deal that crafted a unique partnership between the airline and the state.

The financial package provided some stability for Northwest, but a recession in 1991 and competition among airlines put further pressure on the industry.

By 1993, Northwest was floating the idea of bankruptcy due to its continuing debt burden. Ultimately, Northwest employees made wage and other concessions, and lenders renegotiated loans, giving the airline better financial footing.

Northwest’s financial position improved in the mid-1990s, and the airline added flights to six Canadian cities, improved its frequent flier program and expanded electronic ticketing as online booking became popular. Northwest’s fleet grew to more than 400 planes and a partnership with KLM Royal Dutch Airlines increased Northwest’s presence globally.

Northwest’s new $46 million Airbus A320 maintenance base opened at the Duluth International Airport in 1996; Airbus maintenance operations ceased there in 2006. Also in 1996, a Northwest reservation center opened in Chisholm, Minn. Delta still operates that facility as its Iron Range Customer Engagement Center.

Other Northwest-related events had occurred over that same stretch of time that bode well for MSP.

In April 1991, a KLM 747 touched down at MSP. Although international charter operations had previously served the Twin Cities market, the KLM flight marked the first scheduled service by an overseas-based air carrier to MSP.

KLM was a minority partner of Northwest Airlines at the time. The flight from Amsterdam, the Netherlands was greeted by Northwest Airlines’ Co-Chairman Al Checchi, former Vice President Walter Mondale, U.S. Rep. James Oberstar and Gov. Arne Carlson.

Noise mitigation and other MAC milestones

Other important events early in the 1990s included the Minnesota Court of Appeals unanimously upholding a decision that had been made by a Hennepin County jury in a test case over airport noise.

The jury had found that the MAC didn’t directly or substantially violate the rights of three homeowners who lived near MSP. The lawsuit had initially been filed as a class-action lawsuit by more than 27,000 business and residential property owners. To expedite a decision, the courts had ordered the test case.

At the same time, the MAC was advancing plans to provide noise-insulating measures for eligible homeowners near the airport.

The MAC had started insulating schools near the airport in 1981, when it provided window replacement, air conditioning and other improvements at St. Kevin’s school on 28th Avenue in Minneapolis. Eighteen other schools near the airport would receive insulation by 2006.

In 1992 the MAC and the Federal Aviation Administration announced an initial sound-insulation program for 300 homes. The work consisted of improvements that could include window reconditioning or replacement, new doors, wall and attic insulation, baffling of roof and attic vents and central air conditioning.

The program placed MSP among the most responsive airports in the country on noise mitigation efforts. Since 1992, the MAC has spent $512 million on noise mitigation.

At MSP, work was also underway in 1995 to reconstruct and extend the length of Runway 4-22, which runs diagonally from the southwest to the northeast, to improve the safety and capacity of that airstrip.

Dual track study underway

In 1989 the MAC began the dual track study at the direction of the State Legislature. Lawmakers wanted to determine if MSP should be expanded at its current location or if a new airport should be built in southeastern Dakota County, near Rosemount.

The study resulted from pressure by opponents of aircraft noise in the neighborhoods near the airport and MSP’s growth projections showing the airport could outgrow its existing site.

Over the course of seven years, the MAC and consultants ran various models of passenger demand and airfield configurations to gauge the feasibility of an additional runway at MSP.

Meanwhile, analysts calculated the cost of building a new airport, an idea that met increased resistance from Dakota County residents and politicians. Later in the evaluation process, the idea of remote runways and a small terminal south of Rosemount -- connected to MSP by high-speed rail -- was also briefly considered.

State lawmakers aimed to choose between an expansion of MSP or a new airport by 1996.

The dual track study came to a head that year as the MAC board voted 11-3 to recommend the expansion of the existing airport instead of moving to a new location.

Northwest Airlines and the downtown Minneapolis business community had been opposed to relocating MSP International to the edge of the southern suburbs.

The dual track study had shown that expanding MSP with a fourth runway, more gates and a new terminal could handle all of the growth forecast through 2020. The study also found that the expansion would deliver the same economic benefits of a new airport, but for $2.2 billion less.

The MAC’s vote sent the issue to the State Legislature, which had the final say on the issue. Legislators later that year approved the expansion plan for MSP.

The result: the $3.1 billion MSP -- Building a Better Airport expansion program.

The MAC had analyzed three proposals for new runways at MSP. The plan chosen involved the construction of a new north-south runway, which today is runway 17/35, running mostly parallel to Cedar Avenue on the west side of MSP’s airfield.

In addition to the runway, other expansion projects at MSP included 42 new gates at Terminal 1, a new Humphrey Charter Terminal, new parking ramps and plans for the addition of light-rail transit at both terminals.

Sources: MAC archive material, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Minnesota Historical Society archives.

2000s

Editor’s note: Following is the ninth in a series of articles on the history of the Metropolitan Airports Commission, which is marking its 75th anniversary this year. Earlier stories in the series are found on this website.)

The 2000s brought big changes to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport – some slowly after years of planning, some quickly after unforeseen events.

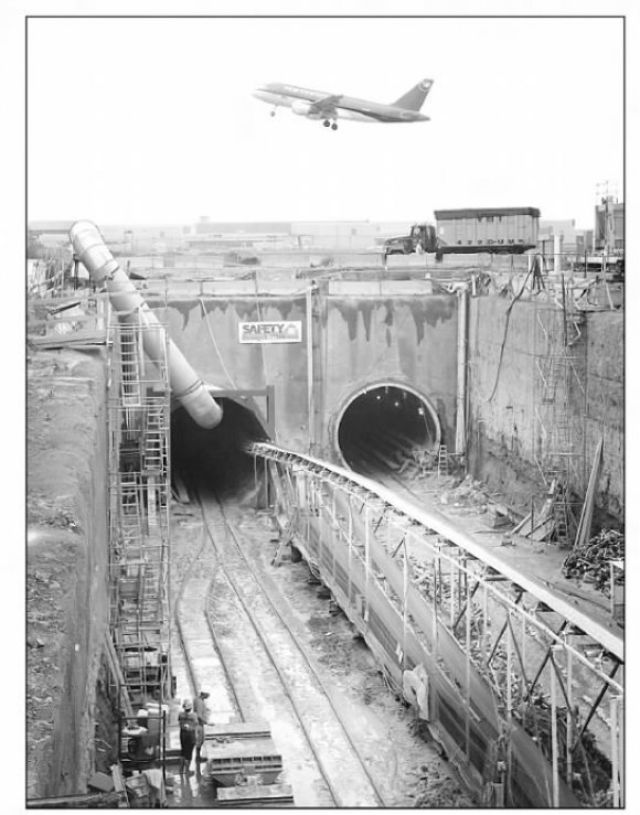

Pictured: The new Blue Line Light Rail Transit tunnel under construction at MSP in 2002.

Work on the new Hubert H. Humphrey Terminal (Terminal 2) had started in 1999 as demand for gates grew and the Metropolitan Airports Commission (MAC) worked to make the local market more competitive.

The terminal plans included eight gates and a Customs inspection facility in the initial construction phase and, soon after, two more gates.

The grand opening took place on May 2, 2001, with a Hawaiian band playing and Sun Country Airlines, Champion Air and Omni Air International planes occupying the gates. The new terminal featured common-use gates, ticket counters and baggage carousels providing shared terminal operations, plus capacity for new airlines, both domestic and international.

There were 24 airlines serving MSP in the late 1990s. Sun Country was in the midst of converting itself from a strictly charter airline into a low-cost scheduled airline, and the new Humphrey Terminal aided that expansion.

The former Humphrey Terminal was razed soon after the new one opened, eventually making way for parking ramps with spots for 10,000 cars.

The 9/11 tragedy

Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport (MSP) was in the midst of a normal Tuesday morning schedule when, at 7:46 a.m. Minneapolis time, American Airlines flight 11 was crashed into the World Trade Center.

The second flight struck the building at 8:03; at 8:37 a.m. flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon and started a fire -- the third hijacked plane to intentionally crash that morning.

U.S. airspace shut down at 8:45 a.m. and all aircraft in flight were ordered to land at the nearest airport as soon as possible.

News of the attacks spread quickly, and buildings considered high profile targets were shut down all around the country. By 8:30 that morning, the Mall of America had put “closed” signs on its doors. At 9:05 a.m., the IDS Center in downtown Minneapolis was evacuated.

The MAC activated its emergency plan; all emergency workers were called in and those already here stayed.

Numerous unscheduled flights arrived at MSP, including two large planes with international passengers.

The ticketing level and mezzanine level of Terminal 1 were full of stranded passengers for much of the day. Airport staff and Northwest Airlines employees worked to provide water, track down hotels with enough space for hundreds of people, and find buses to transport them.

In 2001, few passengers had mobile devices to find another way home, and airport staff and travel agents helped travelers find another way to their destination.

MSP remained closed until Thursday, Sept. 13. Northwest Airlines had planned to restart part of its schedule that day but later delayed all flights until Friday. About 45 planes total took off from MSP that Thursday.

Airports in Boston and Washington D.C. did not re-open Thursday Sept. 13; New York-area airports were briefly open that day but then closed after police arrested a man who tried to get through security with a false pilot’s identification.

Hundreds of parking spaces in the ramps near MSP’s Terminal 1 were off limits after 9/11, as the FAA enforced a rule that unattended cars couldn’t be left within 300 feet of airport terminals. By mid-October, most of the parking spaces were again available.

The airport didn’t run out of parking spaces during the month of restricted parking, as passenger volume dropped sharply after the attacks.

The 9/11 attacks also led to the formation of the Transportation Security Administration, which operates the security checkpoints at airports. Previously, private firms that contracted with airlines or airports had handled passenger screening.

Passenger traffic eventually rebounded at MSP and by 2004 MSP passenger numbers were close to 2000 levels again.

In 2005, MSP recorded its highest annual number ever of passengers, serving 37.6 million – a volume not surpassed until 2017.

Although a deep recession technically started in December 2007, air travel began to slip well before that date as the economy lost momentum. MSP’s passenger numbers declined in 2006 and dipped to 32.3 million in 2009 before starting to rise again.

Construction projects transform MSP

The decision to expand the current airport instead of build a new one somewhere else – decided in the 1990s – led to major building projects throughout the 2000s.

The construction of runway 17/35 started in the spring of 1999 and necessitated the removal of a half-million truckloads of dirt. Sand and gravel was trucked in, and enough cement was poured to build a sidewalk from Minneapolis to New Orleans.

The runway was initially planned to be open to air traffic in 2003. After travel demand declined and airline revenues slumped following 9/11, the runway work was slowed and the completion date moved to 2005.

Pictured: The new runway 17/35, shortly after it opened in October 2005.

The runway’s grand opening in October of 2005 featured a 5K race on the new taxiways and runway. The ribbon-cutting ceremony included MAC officials, Doug Steenland, then CEO of Northwest Airlines, and Chris Blum, the regional administrator for the Federal Aviation Administration.

Concourses A and B were also built in the decade, providing gate access to passengers via jet bridges for regional jets – and taking passengers off the tarmac and out of the elements.

New passenger trams opened on Concourse C and underneath Terminal 1’s parking ramps to facilitate fast, efficient service through the terminal.

The ongoing construction of the Blue Line LRT project attracted media attention, as it stretched from downtown Minneapolis, through MSP and south to the Mall of America.

At MSP, a 100-foot long boring machine produced two 7,300-foot long parallel tunnels 20 feet apart under the airfield.

The new LRT line opened in 2004, providing airport employees and passengers another option for transportation to both MSP terminals. Today, Terminal 1’s station has the highest number of boardings of all the Blue Line’s 19 stations.

Delta and Northwest combine operations

Airlines’ struggles after the 9/11 tragedy continued, and a spike in oil prices following Hurricane Katrina in late August, 2005, also added to the financial challenges.

Delta Air Lines filed for bankruptcy reorganization in September 2005, after not reporting a profitable quarter since 2000. Less than a half hour later, Northwest Airlines did the same.

At the time, Delta was the nation’s third largest carrier and Northwest was the fourth largest.

Over the next two years, Northwest and Delta cut costs, trimmed payrolls and renegotiated debt with lenders to provide financial stability. Delta also restructured its fleet of airplanes and focused more on international flights.

When the two airlines emerged from bankruptcy in the spring of 2007, it marked the first time in five years that a major U.S. airline wasn’t in bankruptcy proceedings.

After exiting bankruptcy, Delta named Richard Anderson as its new CEO. Anderson had been CEO at Northwest up until 2004, when he left for an executive position with United Healthcare.

In 2008, Anderson and Northwest CEO Doug Steenland began explaining to Wall Street and US lawmakers why the two airlines should be allowed to merge.

On April 15, 2008, the two carriers announced a merger agreement.

Testifying before Congress in May 2008, Anderson told lawmakers that the merger would likely lead to job losses at Northwest’s headquarters in Eagan, Minn. However, he pledged to retain other jobs in Minnesota, including thousands of jobs at MSP Airport and 450 at a reservation center in Chisholm.

The two CEOs also addressed lawmakers’ concerns about less competition, job security, reductions in service and fare increases.

Ultimately, the deal passed an antitrust review by the U.S. Department of Justice, as the two airlines’ routes had minimal overlap. The deal was an acquisition of Northwest by Delta, and the new carrier’s combined headquarters were based in Atlanta.

Over a period of more than a year, the two airlines’ merged their operations, including the repainting of Northwest planes with the Delta livery, consolidation of gates in some airports and, in 2009, the merger of Northwest’s WorldPerks frequent flier program with Delta’s SkyMiles program.

In 2013, Endeavor Air – a regional carrier for Delta that had previously been known as Pinnacle Airlines and had an air service agreement with Northwest – moved its headquarters from Memphis to MSP Airport.

Southwest arrives at MSP

In November of 2008, Southwest Airlines announced that it would start service from MSP to Chicago’s Midway Airport -- where Southwest was serving 47 destinations -- on March 8, 2009.

The announcement was another sign of the MAC’s ongoing and increasingly successful efforts to bring more competition to the Twin Cities’ market.

Southwest’s inaugural flight at MSP’s Terminal 2 featured Southwest CEO Gary Kelly, the MAC’s CEO and executive director Jeff Hamiel, Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty, the mayors of both Minneapolis and St. Paul and hundreds of customers and employees.

Southwest now has 15 non-stop destinations from MSP, including five with seasonal service. In July of this year, Southwest began daily service to Oakland International Airport in California.

Sources: MAC archival materials, Minneapolis Star Tribune, St. Paul Pioneer Press, Minnesota Historical Society archives

2010s

(Editor’s note: Following is the 10th and final story in a series chronicling the history of the Metropolitan Airports Commission, which is marking its 75th anniversary this year. Earlier stories in the series are found on this website.)

Signs of improvement for the airline industry